In 1989 the UBC Library was at the centre of a remarkable discovery: a cache of letters by Francis Dickens, the third son and fifth child of the writer Charles Dickens and his wife Catherine Hogarth. The letters, whose existence was unknown until this unexpected find, were evidently part of a bequest to the Library, and emerged in the course of a routine sorting and cataloguing process.

Francis Dickens has little claim to fame beyond his celebrated parentage, having failed at most ventures he attempted. The Canadian Encyclopedia sums up his life with brutal brevity: “His unspectacular career was marked by recklessness, laziness and heavy drinking….”(http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/francis-dickens/).

Francis Jeffrey Dickens, NWMP, 1885. (photo: RCMP Historical Collections Unit).

He did, however, play a role in Canadian history that merits some attention: from 1874 to 1886, he served in the Northwest Mounted Police, and was the officer in charge of Fort Pitt on the North Saskatchewan River during the Northwest Rebellion of 1885.

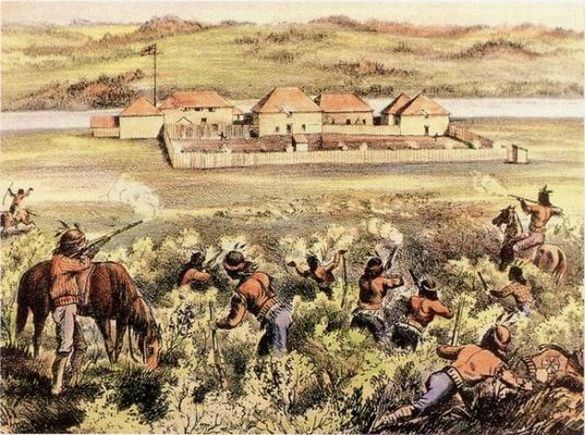

In April 1885, following their success in overrunning the village of Frog Lake, a force of 250 Cree warriors led by Chief Big Bear moved on to threaten Fort Pitt, a trading post protected by 23 members of the NWMP. After an initial skirmish in which one of his men died and another was captured, Dickens withdrew his men, leaving civilian settlers behind as hostages, and retreated to Battleford. Given that he was facing overwhelming odds, Dickens had little choice, and he was commended for his actions.

Fort Pitt, besieged by Cree warriors. From The Illustrated London News – Online at Canadian Military Heritage, Department of Defence, Public Domain

The story of Fort Pitt, and of Francis Dickens’ otherwise unmemorable career, is told in detail in his letters found at UBC , all written to members of the Butts family, who owned a public house Francis had evidently frequented when living in London. The task of editing them for publication fell to Vancouver author Eric Nicol, a graduate of UBC and at one time a lecturer in the English Department. Dickens of the Mounted: The Astounding Long-lost Letters of Inspector F. Dickens NWMP, 1874-1886 was published by McLelland and Stewart and first reviewed by the Globe and Mail on April 1, 1989.

The letters won praise for the vivid picture they gave of life in Canada at a particularly fraught time in its history, as well as the insights they provided into the character of Francis Dickens, about whom very little is known. However, as readers familiar with Eric Nicol’s other writings will have guessed, the real author of the letters was Nicol himself, whose re-creation of life on the Canadian frontier, while based on historical fact, is a wry and amusing imagining of what Francis Dickens must have encountered in his ill-suited role as a police officer. At the time of the book’s publication, Eric Nicol had established himself as a leading Canadian humorist, having won the Stephen Leacock Medal for Humour three times. UBC alumni would also have recalled that in his student days Eric Nicol had been a long-time contributor of humorous columns to the Ubyssey under the pseudonym of “Jabez.”

Eric Nicol. (Photo credit: Barry Peterson and Blaise Enright)

The book has all the trappings of a serious scholarly enterprise: an earnest preface, footnotes, and appendices; and Nicol blends fact and fiction very effectively, so that even the wary reader may be caught off guard—only a Vancouver reader might wonder about the passing reference to the Dickens biographers Hastings and Main. Other clues are perhaps more obvious, such as Francis’ account of his meeting with Sitting Bull, who asked him to autograph a copy of Oliver Twist; or his conversation with Major Harry Flashman, hero of the many exploits recounted by novelist George MacDonald Fraser.

In his preface Nicol quite properly thanks the many people who assisted him in his endeavours, including Charles Forbes, then the Colbeck Librarian; George Brandak, Manuscript Curator in Special Collections; and Basil Stuart-Stubbs, Director of the School of Library, Archival, and Information Studies at UBC. What follows is George Brandak’s account of how Francis Dickens’s letters were presented to the world, and how they were received.

Frances Woodward wrote me that you wanted more information about Eric Nicol’s hoax in pretending that the long-lost letters of Dickens of the Mounted were the letters of Francis Dickens and not written creatively by himself.

The book jacket includes a photograph of Eric Nicol in the Special Collections Division of the UBC Library looking at a folder of letters that were apparently written by Francis Dickens. I gave him a box and folder of letters inserted into mylar that could be assumed to be those of Francis Dickens. Somewhere else there is a photograph of Eric and I looking at the letters. I did play along with his joke. I assumed that people, as they glanced at the letters [reproduced] on the book jacket, would realize they were the creative work of Eric Nicol. The first line of the book jacket, “It was not the best of times, it was not the worst of times, it was Ottawa,” and the sentence that follows on the jacket—“These words, which open this book, could come from only one pen– that of a Canadian Dickens”—should have given away the fact that the book was fiction.

But it did not. Two days after the Toronto Globe and Mail did a review of the book on April Fool’s Day, I received a phone call from a Winnipeg institution asking to visit us to see the letters. I asked the caller on what day the review was printed, and he said, “Oh my God.” A secretary from RCMP headquarters in Ottawa phoned and said her boss had told her to read Dickens of the Mounted because it embodied the spirit of the RCMP much better than any other histories and she wondered whether it was true or not. I assured her that it was fiction and she said, “That is what I thought, but I won’t tell my boss.” As late as 1996, seven years after the book was published, I was drafting responses for the University Librarian who was replying to requests as to the authenticity of Eric’s novel. One person even wanted the UBC Library to re-imburse him for the cost of the book as he purchased it assuming it was fact not fiction because the authentic letters were in the UBC Library. Carolyn J. Moss also wrote the Library to find out whether or not it was a hoax and then wrote a book review on Dickens of the Mounted in the Dickensian, Winter

1997, No.443 Vol. 93 Part 3.

To conclude, Eric wrote me an interesting letter in 1991: “Okay, okay–why didn’t you stop me, when we had the chance? Oh no, you had to let me blunder into that dreadful hoax. Frank Dickens now haunts me, nightly, like Morley’s ghost to giggle and stammer “Th-th-th-anks, Nick, for the f-f-f-avour.” Miserable little twerp. Ultimately Francis Dickens will get all the credit for the bloody letters he never wrote, never could have written, the silly ass. Aside from that, I wish you a happy Christmas. Eric.”

(From an email to Eric Damer and Herbert Rosengarten, February 8, 2007)

George Brandak. (UBC Historical Photograph Collection, UBC 1.1/13424-1)

The Dickensian review to which George refers, written by Carolyn J. Moss and Sidney P. Moss, gives a favourable account of the book’s revelation of the “rich inner and outer life one would not imagined Frank to have had,” but then reveals that the letters are a hoax—albeit a brilliant one, thanks to their success in capturing the life of the Mounties and the idiosyncrasies of Francis Dickens. Indeed, the reviewers describe it as “one of the finest hoaxes of the century.” In the same vein, William French in the Globe and Mail (October 14, 1989) felt it would serve Nicol right “if Francis Dickens is awarded a posthumous Leacock Humour Award for 1989.” Regrettably, that didn’t happen.